- Home

- Holly Fitzgerald

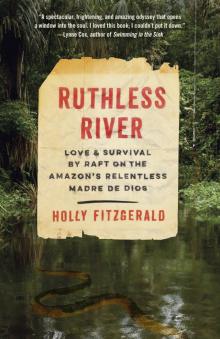

Ruthless River

Ruthless River Read online

Holly FitzGerald

Ruthless River

Holly Conklin FitzGerald was born in Seattle, Washington, and grew up in Woodbridge, Connecticut. She graduated from Lake Erie College and received a master’s degree in counseling from Suffolk University. FitzGerald was a therapist for adults, children, and families for many years before teaching and counseling at Bristol Community College, New Bedford, Massachusetts. She lives with her husband in South Dartmouth, Massachusetts.

A VINTAGE DEPARTURES ORIGINAL, JUNE 2017

Copyright © 2017 by Margaret A. FitzGerald

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Vintage Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and distributed in Canada by Random House of Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Limited, Toronto.

Vintage is a registered trademark and Vintage Departures and colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: FitzGerald, Holly Conklin.

Title: Ruthless river / Holly Conklin FitzGerald.

Description: New York : Vintage, 2017.

Identifiers: LCCN 2016037102

Subjects: LCSH: FitzGerald, Holly Conklin—Travel—Amazon River Region. | Amazon River Region—Description and travel. | Amazon River—Description and travel.

Classification: LCC F2546 .F559 2017 | DDC 918. 1/104—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2016037102

Vintage Departures Trade Paperback ISBN 9780525432777

Ebook ISBN 9780525432784

Cover design by Gabriele Wilson

Cover images: swamp © Pete Oxford/ Minden Pictures/Getty Images;snake © Mariano Sayno/husayno.com/Getty Images; paper © Tetra Images/Getty Images

Map by Robert Bull

www.vintagebooks.com

v4.1

ep

Contents

Cover

About the Author

Map

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Epigraph

Prologue

Chapter 1: Waiting

Chapter 2: The Plane

Chapter 3: Jungle Trail

Chapter 4: Sepa

Chapter 5: Prisoners

Chapter 6: Puerto Maldonado

Chapter 7: Finding a Raft

Chapter 8: Launch Day

Chapter 9: First Day on the River

Chapter 10: The Border

Chapter 11: Flying Free

Chapter 12: The Storm

Chapter 13: Where Are We?

Chapter 14: The Rains Poured Down

Chapter 15: Hope

Chapter 16: The Logjam

Chapter 17: Dead Tree

Chapter 18: Wrestling Match

Chapter 19: Little Balsa

Chapter 20: SOS

Chapter 21: High Noon

Chapter 22: Swimming with Becky

Chapter 23: Log Bed

Chapter 24: Quickmud

Chapter 25: Rant

Chapter 26: Desire

Chapter 27: Butterflies

Chapter 28: Little Moments

Chapter 29: Bees

Chapter 30: What I Want

Chapter 31: Epiphany

Chapter 32: Snails

Chapter 33: Like Sticks

Chapter 34: My Hero

Chapter 35: Marsh Birds

Chapter 36: Rising Fear

Chapter 37: Tiny Frogs

Chapter 38: Time Meshes

Chapter 39: Chasing the Monkey

Chapter 40: Banana Chips

Chapter 41: Barraca

Chapter 42: Maryknoll

Chapter 43: Riberalta

Epilogue

Acknowledgments

Illustrations

To my beloved Fitz and to our family

Many waters cannot quench love, neither can the floods drown it…

Song of Solomon 8:7 (KJV)

Prologue

MARCH 16, 1973

The thumping wakes me. Small, dark shapes bump against the faded sheeting of the pink plastic tent on our balsa log raft. It’s the bees again. They want in.

It’s only about nine in the morning, but already our tent is sweltering. The tropical sun casts an intense circle of light halfway up the thin plastic. I want to open the flap for air, but when I do, hundreds of bees will swarm inside to cover our emaciated bodies like hot moving blankets. They will lap the sweat off our sunburned tissue-paper skin, stinging constantly at our slightest movement.

Slowly, the Bolivian jungle is swallowing us alive.

Struggling to sit up on the maroon nylon sleeping bag, I lean over Fitz. He lies on his side, his back to me. I touch him to see if he’s breathing. He does the same to me when he wakes first, I think, though I’ve never dared to ask.

Last night we held each other, as we do every night after the bees leave and the heat and humidity drop sufficiently for our sticky skin to dry. I listened to my husband’s soft breath as we slipped into unconsciousness, curled in each other’s arms, wondering if both of us would live to see morning.

Fitz’s gaunt face makes him look much older than his twenty-six years. Half hidden by a raggedy beard and mustache, bronzed matted curls spilling around his head, he is still beautiful to me. Whiskers hide his jaw, but I can feel bone, the cavernous hollow of his cheek. Once a stentorian-voiced, tall, and muscular man, Fitz has become a stooped skeleton with sagging skin and a whisper that I must lean in to hear. Not long ago, his walk was so striding I had to skip to keep up. Now we only crawl along our raft, for fear of falling and breaking a leg.

The raft we call the Pink Palace is perhaps eight feet by sixteen feet, hardly bigger than the Toyota we left on blocks in a garage back home. She has no motor. She barely bobs on the muddy water that floods deep into the jungle as far as we can see. Parrots cackle high in the canopy above us, like guests chatting over one another at a party. But Fitz and I are very much alone, trapped in a dead-end channel of the piranha-infested Rio Madre de Dios.

Spaced three to five inches apart, the balsa’s four logs are the only support we have in this landless place. When I sit on them—or the deck, as we call it—looking around me, I see only water rising high up tree trunks. It has spilled, perhaps for miles, in every direction. There is no land anywhere.

In my journal I record our constant ache for food. We have all but surrendered hope on this, our twenty-sixth day of starvation.

Tears well in my eyes. With no fleshy padding, my bones jar against the unforgiving floorboards. I stroke Fitz’s back, still silky under his blue T-shirt, down to his hip and buttock, where muscle used to be. Nothing is left but skin falling loosely over his pelvic bone; his vertebrae protrude like the spine of a gutted fish. Brushing my hand across his body I will him to stay alive.

Our time on Earth is flickering. When Fitz looks at me, he must feel as frightened as I do when I look at him. From what I can see of myself, my stick limbs and fingers, my concave stomach, I am excruciatingly thin.

“Please, Fitz, wake up.”

He doesn’t stir.

“Fitz.” I shake him gently, but there is no movement, and his arm flops when I let it go. A trickle of sweat slips down my back; my heart begins to race. Until this moment, I hadn’t dared imagine that Fitz might leave me here, alone. I thought if we died, we’d die together. I don’t want to face life without him, never again to feel his bear-hug embrace or hear his gravelly “I love you.” I want desperately to believe we have more time.

We’d been on our dream honeymoon in South America months longer than expected. Mesmerized by all we’d encountered, we’d traveled through the Andes by buses, trucks, and trains. Then came th

e jungle.

“Fitz,” I whisper, watching for breath. “We’re going to make it out of here. I just know it.”

Hundreds of bees continue to knock against the tent, seeking a way in.

Where did we go so disastrously wrong?

I know where the fault lies.

Chapter 1

Waiting

ABOUT SEVEN WEEKS EARLIER

If there is a true beginning to our story, it emerges on the rain-soaked unpaved streets of Pucallpa, Peru—a town meant for leaving.

“Hol, remind me why we’re in South America?” Fitz asked, wiping mud from his cheek.

“For the adventure of a lifetime!” I laughed, adjusting the camera bag on my shoulder. I could barely hear myself talk over the hammering rain.

We’d just spent two hours trying to get a stranger’s pickup truck out of a muddy ditch. The truck had been our best hope to reach the rustic airport to buy tickets for a plane south to Puerto Maldonado. We had ten days to get there in time to take the scheduled commercial vessel into Bolivia on the first step of our journey east across the continent. If we missed the boat, there wouldn’t be another for at least three months. We’d been in Pucallpa for three days and were impatient to leave.

Fitz and I held hands as we sloshed through ankle-deep puddles to our hotel, forlorn as puppies in a rain barrel. Sludge and sewage flowed down the street to the swollen Rio Ucayali, a river bordered by rickety wooden huts on stilts. The water had risen up the stilts, making the homes appear to be floating amongst the garbage and rainbow streaks of motor oil swirling on the surface. Vessels huddled together, rain drumming on their metal or drooping palm-thatched roofs.

Other than a few missionaries, Fitz and I were the only gringos in this jungle town. A day downriver were two American anthropologists we’d met while knocking around the Andes. Fitz and I had accepted their invitation to spend a week visiting them and the Iscabacabu tribe they were studying, but we were now back in Pucallpa, ready to fly to our next stop, Puerto Maldonado.

At the cinder-block hotel we changed out of our wet clothes and quickly dressed for dinner. With no screen on the barred window and no mosquito netting for the beds, insects flew in and out as if we were the featured buffet.

The restaurant D’Ono Frio was a short walk from our hotel. The chicken soup seemed a safe bet, but it arrived with rooster feet sticking up from the bowl. I stared at Fitz. “How do I eat these?”

“You don’t,” he said, eyes wide. “Just spoon the broth. Glad I didn’t stray from my usual.” He dug into his favorite, lomo saltado, a simple dish of stir-fried chopped meat and red peppers. Dinner for two came to $2.24.

Fitz was used to shoestring adventure. He’d hitchhiked across the States three times, with little cash in his pocket, before and after Vietnam. Once, he and a friend had clung for hours, screaming, to ropes on the steel bed of a tractor-trailer bouncing through the darkness across New Mexico and Arizona. He could act foolishly, but he sure was lucky. He’d come out fine, not even a bruise. When I had suggested traveling around the world, I wanted a plan and savings to carry us, not just luck. So we worked two jobs each until we’d banked $10,000. By September 1972, we were ready to go, three months earlier than expected, with a rough itinerary in our hands.

I slurped the broth and continued to push the rooster feet around the bowl, not knowing how to hide them, feeling sure they were considered a delicacy.

“That was delicious.” Fitz sighed with satisfaction when he was done with his meal. He set his fork down and stretched back in his chair.

“Hey, don’t rub it in,” I said with a grumbling kind of laugh. I furtively wrapped the rooster feet in a napkin and stuck them in my bag, hoping the cook would think I’d eaten them and not be insulted.

Upon returning to the hotel after supper, and wrapped in a towel from showering in the shared bathroom down the hall, Fitz sat on our bed made of two cots pushed together. Using a chair as a table, he bent over his typewriter, fingers flying. Under the light of a single bulb that dangled midceiling, he wrote about the night downriver when we had encountered the Iscabacabu tribal chief named Morecada. A reporter at the News-Times in Danbury, Connecticut, Fitz had made a deal with his editor to contribute weekly columns during our year of travel. He carried his portable Corona and a stack of foolscap everywhere. The idea was for readers to follow a young local married couple’s low-budget trip across the globe. I was documenting our travels in my journal and with my 35mm Pentax, supplying photos for Fitz’s readers. We’d already spent four months in South America, carefree, still craving adventure.

Fitz pulled out the page, reading aloud: “From the corner of our tent where he crouched, the old Indian leapt to his feet with a shout, grabbed his tribal war club, and lunged toward us.

“ ‘Ya! Ya! Ya!’ shrieked Morecada between the verses of an ancient song of battle, jumping forward and back, forward and back, eyes red with fury, taut bare chest running in sweat, body shaking with violence, hard breath snorting through holes cut in his nose for feathers.”

Morecada had been more than a little frightening in his private performance for us. His tribe had been decimated by the white man. Only twenty-seven members were left.

I brushed my long auburn-brown hair. “I like it. Readers back home will be scared stiff.”

Fitz smiled. “Good. I’m writing Mr. Palmer that this may be the last story for a while. After we leave Pucallpa, communication will be nil. I doubt we’ll find a post office along the river.”

Even in large jungle towns like Pucallpa, communication with the outside world was limited to letters and emergency ham radio. From my pack I took a thin blue aerogram paper that folded into its own envelope, then sat next to Fitz. “I better write my parents, too. I don’t want them worrying if they don’t hear from us for a few weeks.”

Two nights later, our mail posted, Fitz and I learned that the road to the airport had dried sufficiently for use in the morning. We woke before dawn, keen to catch the first bus to the airport and be at the ticket counter before it opened. With flights delayed a week because of the rains, we figured tickets would be at a premium—and we needed to make that boat.

We were first in line. Eventually the line lengthened with men and women—handsome, short, dark-skinned, dark-haired. The barefoot women wore long, colorful hand-loomed fabric skirts and beaded jewelry. I wore my wash-and-dry synthetic dress. Fitz and I, light-haired with blue eyes, looked out of place. At six foot one, Fitz was at least a head taller than everyone else who waited quietly in line. Then chaos erupted when the clerk in his crisp khaki uniform appeared behind the counter. Burly men and women dove between our legs and under our arms, cutting in front of us, shoving us aside. In seconds we were dead last.

“This is crazy,” Fitz yelled, trying to push his way forward.

Within minutes the tickets were sold out. The clerk closed his window, telling us stragglers to return tomorrow for a plane next week.

“We started out first in line!” I wailed. “I can’t believe this!”

I kicked a pebble with my sandal as we waited for the bus back to Pucallpa.

While eating dinner at D’Ono Frio that evening, Fitz coached me. “Look, if someone pushes you aside, you have to stop them. Stand firm.”

I chewed on tough, nameless meat, served without gravy. “It’s like rugby out there,” I complained. “I feel like a football.”

He worked his lower jaw. “Yeah. You’re light as a feather, Monkey-face, and they’re rough. Let me handle this.” His unusual endearment for me was picked up from Eugene O’Neill’s The Iceman Cometh, one of his favorite plays.

Despite being a brusque New Yorker, Fitz had been the only man to give up his seat to women traveling on South American buses and trains. I was proud of his chivalry. Now we both realized that if we were ever to escape Pucallpa, he’d have to drop his manners. “It doesn’t feel right,” he said.

Come morning, Fitz was fifth in line for tickets. When the clerk

entered, two muscular women, wearing geometric-patterned skirts stuffed with petticoats, came at Fitz from behind, trying to slide past him. He lowered himself to their height and extended his arms to stop them.

They tried again but couldn’t get by him.

A third woman came in from the left, with cloth bundles on her back that she shook from side to side. She hurled herself against Fitz, bouncing off him. He stretched and blocked her using his legs and my camera bag as he closed in on the counter. Gasping, he reached it and clung to it as if it were a lifeboat. When he relaxed just long enough to wipe his brow, a woman came up between his legs. He squeezed his long legs around her torso and kept her where she was.

“Quiero dos entradas, por favor, para Puerto Maldonado,” he blurted to the clerk, resolute and standing as tall as he could while scissor-holding the woman. He received the coveted tickets for a plane leaving in five days.

We killed time borrowing books from the North American Mennonite mission library, shuffling back and forth through dripping humidity. Reading most of the day in our tiny room, we waited for the sun to go down. Sometimes Fitz and I trekked to the central plaza marked by a cement tower with a broken clock overlooking the harbor. There we saw children jump into the river from shaky porches or tool around in dugout canoes, oblivious to the dangers lurking below the surface.

Ruthless River

Ruthless River